Inclusion and the Tiger Woods Factor

NOTE: This article on the false sense of inclusion inspired by the popularity of Tiger Woods was originally published in the Diversity Central online magazine, August 2001. Public sentiments about Tiger Woods have changed several times since then.

“To succeed in this organization, you have to play golf.”

“You have to be a tall, white man who tells jokes and plays golf.”

“You have to be a white guy who plays golf.”

“It helps to be white, and it helps to be a guy, and it helps to play golf.”

In focus-group interviews in organizations across North America, golf keeps coming up as part of the perceived success profile of people who get ahead. From the frequency and nature of the responses, it is clear that many people believe golf is one of the non-performance-related routes to success in their organizations. Many non-golfers, white men included, feel this puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to receiving promotions and choice assignments or “just getting in good with the boss.”

A story from a young Asian woman illustrates what seems to be a common experience:

Our boss used to invite people from all over the world for quarterly

meetings. He would always schedule a few afternoons of golf without

checking with anyone. None of the women played, and very few of the

men from outside the United States. It seemed like just a

select group of white men were included.

After a few experiences, the rest of us decided to bring this up in our

meeting, and we told him we were feeling excluded. He acted

surprised! It was only a game and fun with the boys!

While the golf afternoons didn’t cease, I must give him credit for

organizing more common-interest activities like hiking and bicycling.

To people engaged in golf-related recreational networking, these afternoons on the links may seem like just fun and games, but to people who see lost opportunity for “face-time” with potential benefactors, mentors and colleagues, it feels like exclusion.

Tiger has changed the complexion of golf… or has he?

Complicating this issue of golf and exclusion is the nearly universal popularity of Tiger Woods, widely regarded as the most recognized and admired person living on the planet. [NOTE: This article was written and published in 2001–RG]

As this article goes to press, Tiger is honing his game for an assault on his fifth straight major tournament victory, the U.S. Open, held this year at Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma. With his celebrated multi-racial heritage, Tiger has become an icon for the expanding acceptance of golf and the expanded enfranchisement of golfers of all races, genders and ages. In fact, in a web-based search for diversity-related golf articles, 13 of the 23 listed articles carried Tiger’s name in their titles.

Thanks to Tiger, golf is experiencing unprecedented levels of interest and participation from African Americans, Asians and young people. Tiger has also been a strong supporter of his friend and former Stanford University roommate, Casey Martin, who recently won a Supreme Court judgment based on the Americans with Disabilities Act. Martin, who suffers from a degenerative leg condition, is now permitted to use a golf cart in professional tournaments. Another friend and former Stanford teammate of Tiger’s, Notah Begay, is the first Native American to play major tournament golf.

The broad appeal of Tiger and his friends has made golf a new point of connection among people. When Tiger says he wants to help make golf “look like America,” people respond in droves. At his youth golf clinics around the country, people of all races, genders, nationalities, ages and political persuasions line up to take part. Everyone knows who Tiger is and what he does, and what he stands for.

Ironically, the success of Tiger in broadening the appeal and accessibility of golf has served to increase the discomfort many people feel about being excluded by the “golf culture.” Because golf has become more politically correct and socially acceptable, there is not just more golf-talk around the water-cooler; there is also an upsurge in corporate golf outings, charity golf tournaments, work-related golf leagues, and informal golf foursomes. But even with the broad surge in interest, golf remains a mostly white, mostly male pursuit. A few more formerly excluded people are now playing, but for the remaining majority of non-golfers, there are now many more occasions to be excluded from golf.

Breaking through the “grass ceiling”

Some sales people have found that an invitation to play a round of golf at a highly regarded and/or expensive and/or exclusive golf course is a good way to get four or five hours of quality “face time” with a hard-to-corner customer. For this reason, many insurance agents maintain memberships at exclusive country clubs, and many sales organizations maintain corporate memberships for the use of their salespeople.

For many years, African Americans, Jews, women and others have routinely been denied membership at exclusive clubs and therefore denied access to this valuable business tool. While the social aspects of this exclusion are serious issues as well, the restraint-of-trade aspects have provided legislative and judicial backing for opening the membership rolls of many clubs. Today, while some persist in unspoken discrimination and exclusion, few if any country clubs in the United States openly restrict membership on the basis of race or ethnicity.

Gender discrimination is a different story. At many golf courses, public and private, women are routinely barred from preferred tee-off times and from membership on traditionally male committees. In Breaking the Grass Ceiling: A Woman’s Guide to Golf for Business (1998), author Cheryl Leonhardt says:

“Many country clubs are still culturally in the fifties. When the high courts considered the value of equality, they also considered the rights of privacy and freedom of association, ruling that private clubs were exempt from the Civil Rights Act of 1964. So it is often the men who have the preferred weekend morning tee times while the ladies have weekend afternoons. It is the men who hold office; it is the ladies who decorate the clubhouse for parties. It is the men who decide where the forward tees shall be placed; it is the ladies who must hit from them.”

“A good walk, spoiled.”

Mark Twain, one of the nation’s earliest champions of inclusion, had a different view of the situation, as his words, quoted above, indicate. He felt golf was a foolish waste of time. President John F. Kennedy, himself a frustrated golfer, shared Twain’s view, despite his love for the game. Kennedy has been widely quoted as saying, “Anyone who golfs in the low 80s is obviously neglecting something important.”

For most participants, golf is not an elitist way to pursue business but an escape from it. The weekday sign-up sheets and reservation logs of public courses in metropolitan areas are filled with Smiths, Joneses, Palmers and Sneads—pseudonyms of slackers (rhymes with hackers) who have left their offices to “make a few sales calls,” “visit a prospective client,” or “do research.”

Many expense-account-approved golf outings between supplier and customer are not used as sales opportunities or exercises in relationship-building but as mutually collusive “boondoggles” by fellow golfers. They use their business relationship as an excuse to pursue their passion for playing golf, not the other way ‘round.

Whether being excluded from this kind of easy-going camaraderie is a hindrance to a non-golfer’s career is certainly debatable.

Is there a solution?

In some organizations, the response to complaints about golf being part of the necessary success-profile has been to offer lessons in golf skills and golf etiquette to all who are interested. Ernst & Young sponsors a program called Golf-In-Schools for young people throughout the New York area. In describing it, Ernst & Young’s director of Minority Recruitment and Retention says,

“The Golf-In-Schools Program gives inner-city students the framework for the kinds of skills they will need in the business world.”

Unfortunately, programs like this do not address the larger issue of organizational cultures that seem to favor some people over others. Instead, these programs seek to train people not cut from the traditional mold to fit in to the existing culture. They can help more people achieve inclusion and are therefore valuable, but these programs must not be mistaken for culture-change programs. They are actually status-quo programs.

While golf can be a wonderful experience, it is not for everyone. Some people are not physically able to play it. Others may have emotional or intellectual objections to it. Learning proper golf etiquette will not make them more comfortable in a golfing organizational culture; it will only serve to make the golfers more comfortable with them.

To create a more inclusive workplace, organizational leaders who are golfers need to reflect on how much mentoring, networking and “face-time” they are providing on the golf course. They must find ways to provide just as much mentoring, networking and “face-time” to non-golfers, and with the same quality of easy-going camaraderie.

While golf is certainly an instrument of exclusion in many organizations, it often is not as exclusive or as significant as many non-golfers believe it to be. In many cases, what gets dismissed by the members of the “old golfers network” as just harmless fun and games is in fact just that—harmless fun and games.

It may help non-golfers to realize that many of the golfers probably are “neglecting something important.” It may help the golfers to realize that as well, and make sure they are not neglecting the needs of their workplace and its workforce.

Tell me a story about getting vaccinated

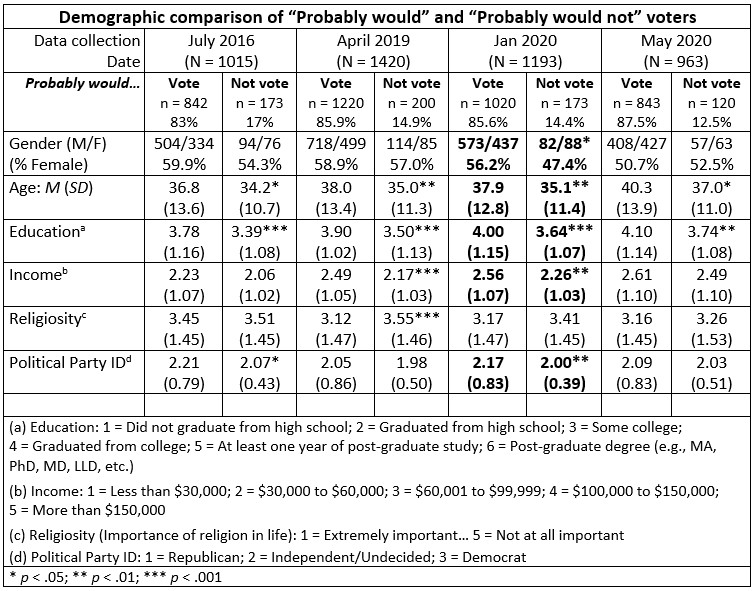

To test the effects of different vaccination advocacy message strategies on attitudes toward HPV vaccination, we randomly assigned study participants (N = 963) to one of four different message-strategy groups:

(1) The Narrative Strategy–A short story about a parent, Mark, who takes his 11-year-old daughter Emma to the doctor. During the visit, the doctor recommends that Emma receive the HPV vaccination. Mark is at first hesitant, but after considering the facts the doctor tells him, he decides to get Emma vaccinated. Afterward, they go for ice cream.

(2) The Informative Strategy–A fact-and-figure-filled overview of the case for HPV vaccination based on reports from the CDC, including the range of cancers the vaccination would prevent, the number of lives it would save, and its excellent safety record.

(3) The Expert Strategy–An appeal from a doctor with an impressive-sounding title asking for support in gaining acceptance for HPV vaccination, citing similar facts and figures from CDC reports. Accompanying the appeal was a photo of a distinguished-looking male doctor.

(4) The Non-Expert Strategy–An appeal from a school PTA member asking for support in gaining acceptance for HPV vaccination, citing the exact same facts, figures and rationale as the appeal from the expert doctor. Accompanying the message was a photo of a young mother with a small daughter on her lap.

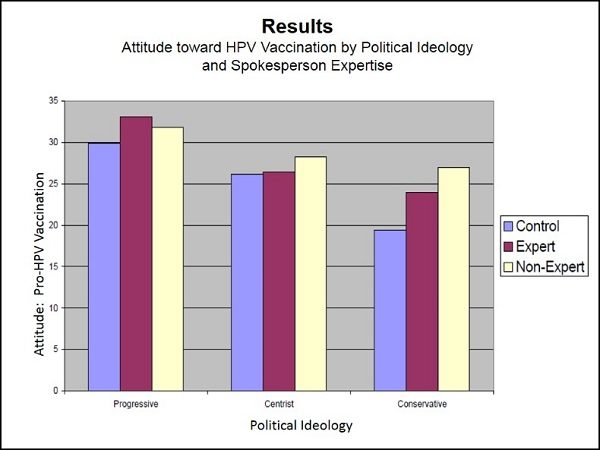

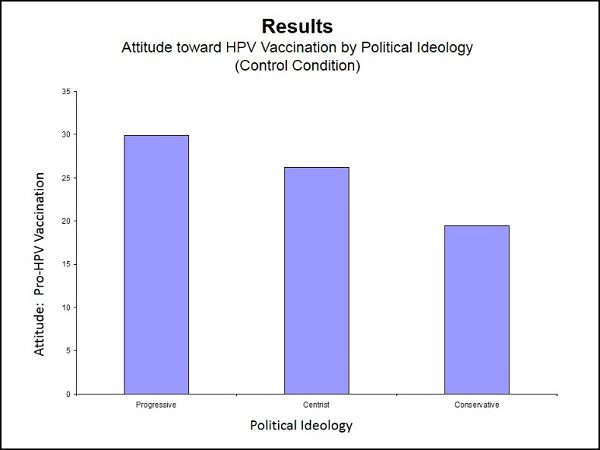

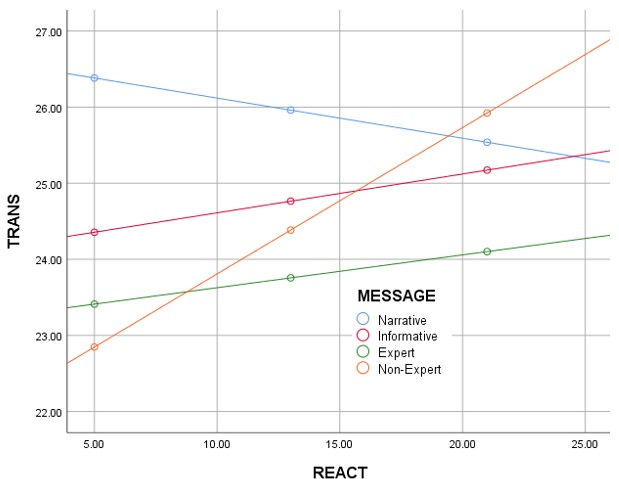

As illustrated in the graph above (Figure 1), when the vaccination advocacy messages focused on factual reasons for supporting HPV vaccination (as in the Informative, Expert spokesperson, and Non-Expert spokesperson message strategies), reactance (i.e., resistance) increased as transportation (i.e., emotional engagement with the message) increased. But when the message was delivered as a narrative story about one person’s HPV vaccination decision, reactance declined as transportation increased.

Resistance is persistent and problematic

HPV vaccinations are safe, readily available, and if universally administered would prevent countless cancers and save 4,000 or more lives in the U.S. every year. But at least 25% of the parents who receive vaccination recommendations from their doctors decline to have their children vaccinated.

Source: CDC (2019) Vaccine for human papillomavirus.

As the graph above (Figure 1) suggests, receiving vaccination advocacy recommendations from an informative source or an expert figure like a doctor produced significant amounts of resistance, with greater involvement in the message producing greater levels of resistance. Receiving those recommendations from a non-expert figure amplified this effect. But telling a story about a parent overcoming doubts to support HPV vaccination seemed to reverse this effect, with greater involvement in the story producing reduced amounts of reactance.

Analyses

The message strategies were modestly effective in producing positive attitude change: Post-Test Attitude – Pre-Test Attitude Mean Difference = 1.41 (SD = 3.81), t (935) = 11.34, p < .001. While there was no significant difference in attitude change between the messages, F (3, 932) = 0.79, p = .787, examination of the underlying factors contributing to attitude change revealed significant mediating effects of transportation and moderating effects of reactance.

While the direct effect of the different message strategies on attitude change was negligible, F (4, 931) = 2.08, p = .081, the indirect effect including the potentially causal mediating effect of transportation was quite significant, with greater levels of transportation producing greater change in attitude, t (933) = 2.75, p = .006. Greater levels of reactance, on the other hand, produced less and in fact negative change, t (933) = -4.92, p < .001.

Transportation vs. Reactance

With each of the typical persuasive message strategies that used facts and figures to achieve compliance with vaccination recommendations, as transportation (i.e., emotional engagement) increases, so does reactance (i.e., resistance), illustrated by the parallel lines that rise going from left to right in Figure 1. This increase in reactance limits the effectiveness of those messages to influence positive changes in attitude toward vaccination.

With the narrative strategy, on the other hand, increased emotional engagement with the story was associated with reduced reactance. This suggests storytelling may be an effective means for overcoming or avoiding resistance to vaccination when more directive strategies fail.

HPV Vaccination Background

Widely known to be the primary cause of cervical cancer, which kills more than 4,000 women in the United States each year (U.S. Cancer Statistics, 2019), HPV infection also causes cancer of the anus, penis and throat in men, and genital warts in both sexes (CDC, 2019). The infection is so widespread as to be considered of epidemic proportion. In the U.S., 80 million people (about one in four) are currently infected with HPV, 14 million more become infected each year, and nearly 35,000 people each year are affected by a cancer caused by HPV (CDC, 2019).

A widely available, easily affordable vaccine that would prevent 92% of HPV infections has been shown to be safe and effective (CDC, 2019), and the rational, socially responsible, utilitarian case for universal vaccination against HPV seems highly persuasive. However, acceptance and utilization of the vaccine have been far from universal. Barely half of 13-to-17-year-old adolescents in the U.S. are up-to-date on their vaccinations against HPV (Walker et al., 2019), and reports suggest that the percentage of parents actively choosing to resist having their children vaccinated against HPV is increasing (Darden et al., 2013.)

Explanations for the continued resistance and strategies for overcoming it are needed. The effects of reactance may be part of an explanation, and storytelling strategies may be part of the solution.

References

CDC (2019, August 2). Vaccine (shot) for human papillomavirus. Retrieved on March 17, 2021 from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/diseases/hpv.html

Darden, P.M., Thompson, D.M., Roberts, J.R., Hale, J.J., Pope, C., Naifeh, M., & and Jacobson, R.M. (2013). Reasons for not vaccinating adolescents: National Immunization Survey of Teens: 2008 – 2010, Pediatrics, 131, 645-651. Available online at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2013/03/12/peds.2012-2384

U.S. Cancer Statistics (2019, June). Leading cancer cases and deaths, female, 2016. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on November 2018 submission data (1999-2016). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. Retrieved from https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html

Walker, T.Y., Elam-Evans, L.D., Yankey, D., Markowitz, L.E., Williams, C.L., Fredua, B., Singleton, J.A., & Stokley, D. (2019, August 23). National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6833a2.htm

Marginal voters more likely to vote for Democrats in 2020

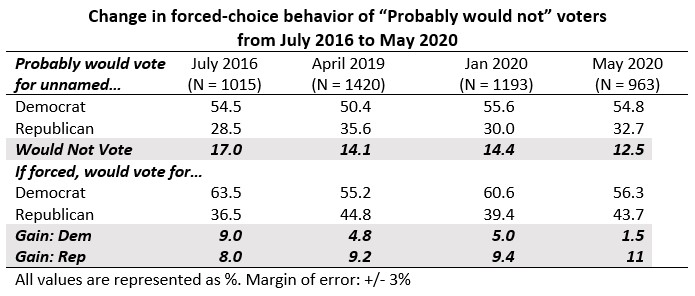

In four separate surveys conducted over the last four years, thousands of U.S. residents 18-years of age and older were asked to indicate whether they would vote for an unnamed Democrat or an unnamed Republican in an upcoming election some years in the future. Based on the trends suggested by these surveys, it appears more marginal voters are likely voting in the 2020 election, and most of them are likely to vote for Democrats.

The percentage of respondents who said they “would probably not vote” has gone from 17.0% in mid-2016 to just 12.5% in mid-2020. The party orientation of those who would probably not vote (determined by their indication of their vote-choice if forced to vote) suggests far fewer Democrat-leaning voters plan to sit out this election than Republican-leaning voters.

Adding the forced choices of “would-not-vote” respondents to the total vote counts adds just 1.5% to the total for the unnamed Democrat (from 54.8% to 56.3%) but adds 11% to the total for the unnamed Republican (from 32.7% to 43.7%).

Average voting percentages in Presidential elections in the U.S. have hovered in the 60% to 65% range for several decades. These results suggest an extremely high turnout for Democrats (i.e., 98.5%), with few opting not to vote. They also suggest a high turnout for Republicans (i.e., 89%), but with seven times as many Republicans remaining on the sidelines as Democrats.

[NOTE: Samples drawn from Amazon Mechanical Turk virtual workforce, which skews younger, more highly educated, lower in income than the average of the U.S. population.]

3 simple strategies to sway people who don’t want to listen

Are Democrats just bad at communication?

Consider all the hand-wringing after the release of the Mueller Report. There were 448 pages of documented evidence of shady dealings by a presidential candidate and his minions before and after the 2016 election and the 2017 inauguration.

Before and after its release, Democrats in Congress, on talk shows, and in the press touted the findings of the Mueller Report virtually non-stop for nearly two years.

And the president’s approval ratings went from approximately 42% before the release of the report to approximately 42% afterward.

Does this mean that Democrats’ messaging about the contents of the Mueller Report was poor communication?

Not really.

There was a great deal of Democratic eloquence that was much appreciated by other Democrats. But that eloquence went unheard and/or unappreciated by just about everyone else.

If Democrats’ intent was to sway the opinions of people who were not Democrats, then the messaging was ineffective. Not necessarily bad. Just ineffective.

Why?

Well, if we divide the world of non-Democrats into two groups–Republicans and Independents–the messaging of the Democrats may have been eloquent but it was poorly constructed and targeted to reach those non-Democrat audiences.

Republicans tend not to be interested in anything Democrats have to say because Democrat messaging typically revolves around how wrong Republicans are. And not just wrong, but often evil, mean-spirited, uninformed, misled, immoral, and an existential threat to the founding principles of American democracy.

Who wants to pay attention to attacks on their character?

Independents tend not to be interested in anything Democrats have to say because Independents are just not very interested in politics, and especially not partisan politics (except when it smacks of scandal or World Wrestling Federation-style entertainment).

So, how could Democrats communicate their messages to these audiences? Here are three research-based* ways to reach people who just aren’t interested.

1. Repetition of Short Simple Phrases. Even when you’re not paying attention, things that are repeated over and over seep into your awareness. Once you’ve heard “Crooked Hillary” for the 1000th time, the words start to seem like they belong together.

“Most corrupt president in history” was a frequently repeated phrase at the most recent Democratic presidential debate. That might be a little too wordy and polysyllabic for maximum effectiveness, but the repetition is on the right track.

Repeated showings of video clips with repetitive messages like this one can also be effective, especially if captioned with an easily remembered phrase such as “He reaps what he sows.”

2. Emotionally Charged Images. Logic may be the favorite persuasive tool of intellectuals, but logical arguments never win the opposing side’s hearts. Emotional images avoid the logic trap. They stick. They also work best when combined with repetition and short, memorable phrases.

For instance, imagine the power of a photograph of one or more of the children who were separated from their parents at the southern border and held in cages? Imagine it shown with a caption of “Who locks up innocent children?”

Or a photo of a downcast Kurdish family in the ruins of their home with a caption of “Who abandons their allies?”

3. In-Group Tribal Spokespeople. Republicans don’t listen to Democrats, but they do listen to Republicans or people they believe speak for their view of the world. This makes Mitt Romney a potentially powerful figure in American politics as the year 2019 comes to a close.

Mitt may not speak to or for everyone, but thanks to the magic of videotape, other prominent Republicans can be used to deliver important messages to Republicans. One example is this clip of Senator Lindsey Graham describing what he considers an impeachable offense.

Can Sean Hannity or Rush Limbaugh be moved to speak truth to power, or about it? Stay tuned.

* If you’re interested in the research on which these suggestions are based, feel free to get in touch.

What happened to the middle?

1 = Strong Republican

2 = Not Strong Republican

3 = Lean Republican

4 = Independent/undecided

5 = Lean Democrat

6 = Not Strong Democrat

7 = Strong Democrat

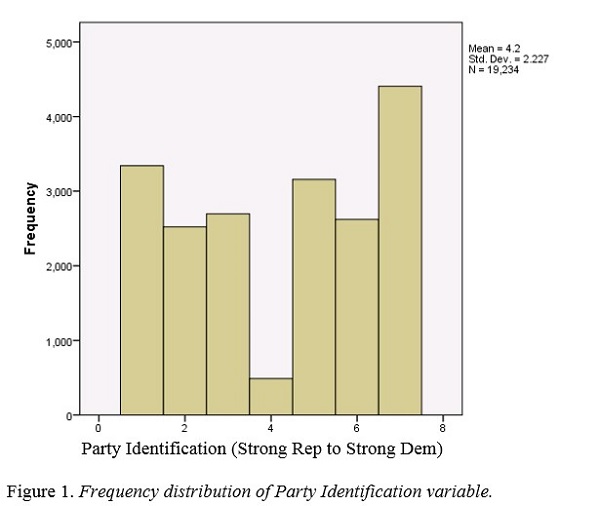

We hear a lot about political polarization these days.

Editorial pages and pundits and Uncle Fred on his Thanksgiving Day soapbox express quite a bit of wishing that our politicians would pay more attention to the reasonable, norms-loving moderates in the middle.

But is there anybody there?

In his book, The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans (2009, U of Chicago Press) Matt Levendusky suggests that almost everyone has chosen up sides.

To make it easier for inattentive, unstudious, and busy-with-other-stuff normal folks to figure out which party more closely aligns with their worldview, party leaders have redefined and amplified the differences between what it means to be Republican and Democrat.

And, especially lately, they’ve also implied that the opposing party is an existential threat to “our” way of life.

Now, before you go “so I guess that means people should be more attentive and studious about politics,” there’s some convincing research suggesting that the more you pay attention to politics, the more partisan you get.* So maybe that’s been happening too.

Either way, while our sentiments may make us wish for a return to a comforting centrist sensibility in our national politics, it looks like we’re running short on centrists to lead that return.

Normally, the distribution of almost anything along any continuum forms what is called a “normal curve,” with the fattest part in the middle of a relatively symmetrical arrangement of whatever population of people or things or other data points have ben measured. And the larger the population, the more “normal” the arrangement tends to be. The chart shown in Figure 1 was constructed using data from a recent American National Election Survey (ANES). It shows that, where politics are concerned, things are no longer normal.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the values for political party identification exhibited almost a perfect reverse of a normal distribution.

This may have been a function of the survey question, which asked respondents to identify themselves as one of the following: “Strong Democrat,” “Not Strong Democrat,” “Lean Democrat,” “Independent/other/undecided,” “Lean Republican,” “Not Strong Republican,” or “Strong Republican.”

Apparently, partisans did not seem to want to characterize themselves as “Not Strong.”

And hardly anyone was willing to be “Undecided.”

* Check out the work of Markus Prior

On encountering another smartest person in the room

Are you in the right room?

One of the problems with being the smartest person in the room is you too often expect no one else in the room will have anything of value to add, and that <sigh> you will have to expend soooo much energy getting those people who keep speaking up to just stop talking and listen to you and understand that yours is the only sensible solution.

I’ve been the smartest person in the room enough times to appreciate that.

But one of the other problems with being the smartest person in the room is your automatic response to treat other people’s ideas and thoughts as inferior competitors to your own—to be ignored, or shouted down, or rebutted—instead of contributions that just might add some value.

The unfortunate result is that you never get the benefit of that potential added value. You are condemned to produce work that is only as good as what you can envision yourself—or would be that good if only everyone else would cooperate.

And you never get to experience producing work that is better than you could have imagined if you hadn’t limited yourself to being the only valid source of vision and ideas.

Welcome to my world

I still find myself in situations where I feel like I’m the smartest person in the room. (As a college professor teaching undergraduates, sometimes it feels as though I’m the only awake person in the room.)

But I’ve learned a few things in recent years, and they were not all easy lessons.

Sometimes I’m not the smartest person in the room. (Statistically not likely, but at least once in a hundred rooms it is probably true.)

Even when I am the smartest person in the room, several people in the room probably know more about some things than I do. (Contemporary music fans and TikTok users come to mind immediately.)

While I may be extremely, incomparably, brilliantly smart, my intelligence does not cancel out the value and wisdom carried by everyone else. A three-year-old toddler knows more about some things than I do. I have blind spots. I also have “I didn’t consider that” spots.

Whose ideas will really win?

I have many really, really smart ideas. They might, in fact, be better than all the individual ideas of everyone else in the room. And if life was a competition with prizes for each room’s best individual ideas, mine might win.

But most work projects—and most human interactions (and most lives)—are not individual competitions. Every single one of my really, really smart ideas can probably be made better by adding value from other people’s ideas. Or to them.

Of course, I can’t envision it, because I’m only as smart as I am. If I were smarter, I might be able to see that, working together, we can create something better and greater than any one of us can envision. Even the smartest person in the room.

Marketing Objective #1

Marketing 101: To the Navel and Beyond

Whether you’re a for-profit business, a not-for-profit service provider, or a not-making-enough-profit individual, it’s a good idea to do a frequent review of your fundamental marketing objectives and your plans for achieving them.

I’m a fundamentalist at heart. Except when it comes to religion, I think learning and applying fundamental principles on a consistent basis is the surest route to the Promised Land.

(But let’s leave religion alone for now. It presents some interesting marketing challenges, and we can get into a discussion of the difference between fundamentalism and dogmatism, but let’s save it for another time.)

If we’re going to take the fundamentalist approach, let’s start with a basic definition of “the Marketing Concept.” For an individual or organization, it means developing your products and services (including your distribution, pricing and promotion strategies for those products and services) to satisfy the needs and wants of targeted customers as well as your own needs and wants.

The difficulty with fundamentalism is that the fundamentals are so, well…fundamental. They’re so basic that, like the concrete foundation of a building, they can get obscured by all the stuff we pile on top.

Goal #1: Survive and Thrive

To provide the best products and services for its customers and stakeholders, an organization first has to exist. And to provide livable wages and a nurturing environment for its staff members, it must continue to exist.

Customer focus is important, but an organization cannot long provide value to customers if its business plan, or lack thereof, involves killing itself and its staff members. Visit sitemap.

Fundamental #1: Our own wants and needs

Many of my colleagues and clients (mostly in the fields of healthcare and higher education) complain that, when it comes to developing marketing plans, a lot of the leadership decision-makers they work with never get beyond examining their own navels.

I’m not sure they’re even getting that far.

Most often, they’re distracted by their own products or services. They focus on “how can we sell this?” instead of “what does the organization want and need, and how can this new [thing, idea, direction] help us achieve our long-term objectives?”

Or they’re distracted by some new development in the marketplace: a new technology, a new government regulation, a new social media tool, a new competitor. And their response addresses the immediate opportunity or threat without addressing fundamental wants and needs.

Long vs Short

The problem often comes down to a conflict between short-term gain and long-term objectives. Unless an organization’s long-term objectives—those fundamental wants and needs—are clearly defined and consistently revisited, too many decisions will be made strictly on the basis of short-term gain under the assumption that any gain must be beneficial.

Firing half your staff will reduce costs and increase profits on a short-term basis, but it may not be a good decision in the long-term. For a hospital or a community college, there might be short-term gains achieved by adding a new 256-slice CT scanner to compete against that hospital in the next town, or building new dorms to compete against four-year colleges. But would those be the best capital investments if Fundamental #1 was consulted first?

Maybe so. But maybe no.

The Navel Battle

Marketing, according to the American Marketing Association, is all about developing mutually satisfying exchange relationships with customers. Most marketers focus most of their attention on learning all they can about how to satisfy their chosen customers, and rightly so. But many forget that adverb: “mutually.”

The more fully the exchange relationship satisfies both sides, the more successful it will be. Marketers who do not fully appreciate their own wants and needs can only achieve success by accident, and accidents do not tend to last very long.

It is tempting for leaders to insist their staff members focus on satisfying all their customers’ needs, but unless the organization addresses its own needs (and those of its staff members), no one will be satisfied in the long run.

The Last Word on Improving Patient Satisfaction

You’ve improved your patient-care processes and outcomes but you’re still not happy with your patient satisfaction scores. And now, with CMS reimbursements increasingly tied to those scores, the pressure is rising to raise them.

Fortunately, the fields of psychology and behavioral economics may offer some easy-to-implement solutions to improve patient satisfaction scores both coming and going.

Start at the beginning

People’s memories are selective. They remember the beginnings and endings of things far more vividly and intensely than the middles.

The beginnings are particularly important, because they set up the patient’s expectations for everything that is to follow. It’s called “affect priming.”

If the beginning is stressful and unpleasant, the rest of the stay will have much repair work to do. Therefore, it is crucial to address patient satisfaction from the very beginning—the patient’s arrival at the hospital.

Address the parking situation: Worrying about finding a place to park is an issue that affects patients as well as their families. A free valet parking service can remove this worry and help create a caring first impression.

Careful maintenance of parking lots—to make them easily accessible, clean and safe— and liberal parking validation policies will also address this important opportunity to make a good first impression.

Greet everyone with a “Hello, can I help you?” Even people who spend a lot of time visiting hospitals can have a hard time finding their way around. Making every visitor feel welcomed and taken care of must become everyone’s priority.

Specially trained volunteers and/or dedicated staff “Welcome Ambassadors” can make a real difference in visitors’ experience.

Add some branded swag to the intake and admission process: In addition to making people feel welcome, giving them some branded items at intake can help them feel a stronger and more positive connection to you.

The act of accepting the gift of a branded pen (and/or other items such as tote-bags, socks, tee-shirts, baseball hats etc.) creates a sense of endorsement and mutual regard on the part of a patient. (It also helps if the intake and admission process is streamlined and friendly, of course!)

Your Last Chance

Research by Daniel Kahneman and Donald Redelmeier1 has shown the power of happier endings. They found that adding a period of greater comfort to the end of a painful experience influenced subjects to remember their pain levels as less intense.

Even when they made the overall unpleasant experience longer, ending it more pleasantly made the whole experience seem more pleasant.

The takeaway from this research is simple: Making the last few hours of a hospital stay more pleasant can change a patient’s lasting impression of the entire stay.

Here are a few last-day strategies that can pay big patient-satisfaction dividends:

Special last day meals: Food is always one of the most memorable (and not always pleasant) things about a hospital stay. Special meal treats on the last day before discharge, like an extra-specially made desert, can help make patients feel as though they have been treated with special care.

Special last day farewells: It is easy for a patient to feel anonymous, especially in a large institution like a hospital. Post the discharge schedule at all unit stations, and make it a priority for all members of every shift – and every discipline, including support and non-clinical personnel – to review the list and stop in to offer some “goodbye” best wishes.

The 30 seconds it will take will yield long-lasting and highly positive memories for the patient—and for your staff members as well.

Special last day treats and gifts: The same discharge schedule can be used as a distribution schedule for more branded swag items like those mentioned above in association with intake.

Tote bags are especially handy at discharge, especially if they are needed to carry some parting gifts—all carrying your hospital’s logo imprint, of course. Specially branded cookies and cupcakes (decorated with your logo as icing) can also help patients leave with good memories of their stay.

Health care includes showing you care

We’ve all seen studies that show that patients who have good communications with their care-givers rate the quality of care they receive higher. That’s another area worth focusing on for raising patient satisfaction scores (and certainly worth a few future posts).

Good communication makes for good relationships, and both circle back to the “affect priming” mentioned at the beginning of this post. If you show people you care about them on Day One, they will feel more cared about through their entire stay (and afterward, when they answer those HCAHPS survey questions).

You show you care by being interested—genuinely interested—in how they feel and what they have to say. Which means that it’s not enough to start off that first contact with, “Hello, can I help you?”

You also need to listen to what comes next.

References1

Kahneman, Daniel; Frederickson, Barbara L.; Schreiber, Charles A. & Redelmeier, Donald A. (1993) When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401-405.

Redelmeier, Donald A. & Kahneman, Daniel (1996) Patients’ memories of painful medical treatments: real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain, 66(1), 3-8.

Can you punctuate a quote?

How good are you at quotation punctuation?

Everyone who writes news releases for a living knows the value of quotations.

But surprisingly few people graduating from college today can actually punctuate sentences with quotations in them.

Can you?

Here are 10 punctuation challenges. A pro should be able to get all 10 correct.

(1) im proud to be an american citizen said afrim defiantly

(2) our company was founded on the principles of quality and value he said

(3) what do you mean said Johnson raising an eyebrow

(4) responding to the question CEO robert johnson said theres no evidence linking my company to those accidents

(5) you look like you like pizza said luigi you came to the right place

(6) the only difference between my generic product and theirs said johnson is the name on the label

(7) i want you to read the raven a poem by edgar allen poe said the professor

(8) the professor turned suddenly and said I want to make sure you read the raven

(9) have any of you ever read the raven he asked

(10) in a long quotation said professor gans find a way to let the reader know who is speaking as early as possible the professor drank some amber liquid from a flask he had hidden in his pocket and continued no later than the end of the first sentence he said

How did you do?

To download the quiz and answers in pdf form, click here.

Reducing Risky Behavior

Risk Communication Can Be Risky

Environmental Safety and Public Health Policy-Makers Often Make Matters Worse

Communication of science-based information to the general public…particularly health-related information…is a well-studied field.

This may be because it is so often done so poorly.

Many public behavior interventions, especially those based on intuition, “common sense,” political persuasion or religious belief, tend to focus on presenting a rational, logical argument for complying with a specific behavioral request.

Researcher Timothy D. Wilson cites “D.A.R.E.” and “Scared Straight” interventions…famous and widely adopted programs intended to reduce crime and drug use among young people…as examples of programs that “make perfect sense, but… are perfectly wrong, doing more harm than good. It is no exaggeration to say that commonsense interventions [such as these] have prolonged stress, raised the crime rate, increased drug use, made people unhappy, and even hastened their deaths.” (Source: Wilson, 2011, Redirect: The surprising new science of psychological change. New York: Little, Brown & Co.)

Unfortunately, this “boomerang effect” is too common in public policy communications. Public policy communicators would do well to read the government’s own manual on risk communication, which ought to be stapled to every keyboard in every PR department in every science, health and environmental organization in the English-speaking world.

Risk Is Attractive

Nike’s 5-minute animated World Cup commercial urges its audience to “Risk Everything,” basically because the safe route is boring. And clearly, there are a lot of risk-seekers out there.

While the animation and execution are exquisite, the storyline is predictable to the nth degree—but who cares? As an exercise in appealing to its targeted demographic: GOOOAAAAAALLLLLLLL!

The product shots are also very appealing. These are not the soccer cleats I wore in high school, and the shirts and shorts look as though world-cup-worthy pectorals, abs and glutes are included at no extra charge.

All this being said, the spot ought to be worrisome to conservatives, control freaks (including many sports coaches) and public health advocates. The reason it should be worrisome is not because of the spot’s likely influence on an easily-manipulated demographic—actually, soccer players are a rather stubborn lot. This spot is not going to change them in any way except maybe to increase their motivation to buy another pair of cleats.

No, the scarier scenario is that the spot is an accurate reflection of the risk-seeking ethos of an entire generation. In the spot’s storyline, risking everything is the only way to beat the practiced but predictable perfection of the clones (who could also be the minions of the Matrix, or the Man, or your parents).

But in real life, the associated behaviors are:

- Going for the low-percentage spectacular dunk rather than the safe but boring lay-up

- Riding the motorcycle without the helmet

- Not buckling those seat belts

- Not vaccinating your kids

- Not stopping to unroll that Trojan

- Not settling for the status quo

Small wonder so many campaigns aiming to reduce risky behaviors actually serve to increase them. Maybe the control freaks and health communicators would do better if they positioned those undesired behaviors as something other than risky.

How about stupid? Or shameful? Or embarrassing?

As Nike is trying to tell them, risky is just too attractive.